“I built a 777 simulator in my garage”

Kitted out with flight simulator software, parts of a retired Boeing 777 and decades of technical how-know, Gary McCombie proves that if you can’t join the cockpit crew, there’s always another way…

Words: Hannah Ralph

Photographs: Alexander Baxter

17/09/2025

“I grew up about a mile or so from Aberdeen airport,” says Gary McCombie – a man who has built an entire Boeing 777 cockpit simulator in his garage. “My mum and dad would take me there on Sunday afternoons. This was back when you could walk right into departures without a flight or passport or anything. We’d stay for a while, watching the planes come and go.” McCombie didn’t much care where the big birds were headed – for him, it was about how they got airborne at all. “It was definitely a technical kind of obsession. A machine fascination,” he says.

These early memories explain McCombie’s choice of career. A self-proclaimed ‘design guy’, he would go on to become a successful engineer in the steel-making industry. So far, so grounded.

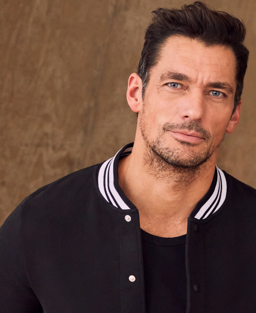

Gary McCombie in his garden in Stonehaven, south of Aberdeen; starting engine two. Opening image: McCombie prepares for ‘take-off’

Rising higher

“I was desk-based for 15 or so years, with just a few holidays to Spain here and there,” he says. That was until a game-changing promotion in 2000 saw him move into technical sales. “Suddenly, I was doing something like 100-150 flights a year, selling the company’s expertise all around the world and project managing the jobs once they were won.”

You won’t be too surprised to hear who McCombie chose to fly with. “I’m a big British Airways guy,” he says. “I remember feeling very proud of my Blue tier membership card. Now, I’m Gold for Life.”

Meanwhile, back at home, McCombie’s post-work obsession was gaining speed via the computer game, Microsoft Flight Simulator. “It had been a birthday present from my mum and dad about 30 years before,” he recalls of that first CD-rom. “I would play it on the PC with a keyboard and a mouse. The graphics were horrendous!”

Small amount of throttle applied for taxiing to the runway; the First Officer’s headset leads and storage bin

A brief history of the at-home simulator

While the early 1980s were a wireframe world for civilian flight simulator software, the 1990s saw major improvements. Microsoft (which dominated the space) added more airports and aircraft to its game, as well as improving the overall realism. In the early 2000s, elements such as 3D cockpits, global ‘scenery’ (the word hobbyists use to describe the virtual environment) and AI air traffic gained traction. Microsoft Flight Simulator 2004: A Century of Flight became a cult classic, and other big players (including Lockheed Martin) entered the market.

McCombie kept up. “It was at this point that hardware companies started getting involved, too,” he says. “You could now buy a Boeing yoke (also known as a control wheel) or Airbus side stick. You could start plugging in pedals and throttle quadrants via USB into your computer. So, every Christmas or birthday, I’d end up adding more physical controls.”

‘Are you still flying a desk?’

But even with his ever-evolving set-up, McCombie was still at his computer. The next leap in realism would take him somewhere unexpected: to Toronto, Canada. “About ten years ago, I became aware of a Canadian company called Flightdeck Solutions (FS) – a leading supplier of fixed-base simulation cockpits,” he says. While these were a world away from the hi-tech simulators used for training by airlines including British Airways, they offered something attainable (and affordable) for civilian hobbyists. “I’ll always remember the FS tagline: ‘Are you still flying a desk?’ So, after much research and a few trips to Toronto, my wife made me a deal: if I get this, she gets to buy a new kitchen. Everyone was a winner.”

The simulator from FS arrived in Scotland in three huge wooden boxes, each weighing around a ton. Inside were two seats (Captain and First Officer), a central pedestal, throttle quadrant, a main control panel and an overhead panel. “I now had all the primary controls required for flying, from the comfort of my shed,” McCombie says.

The sim life takes flight

As for the view, this came courtesy of three 55-inch TVs positioned behind the control panel. “I remember the first night I set it all up,” adds McCombie. “It looked great. My two kids were sitting behind me and, as I banked the aircraft, the eldest lurched and grabbed my seat. Nothing was actually moving, but it was as if you could really feel it.”

It was perfect – almost. “I’d made huge progress, but it wasn’t yet a 360° experience,” explains McCombie. “I could still see the ceiling of my shed, including my son’s bag of footballs in the corner!” It was only when Covid hit that he had a bright idea. “I found a company in South Wales that had taken retired planes from BA, and its public arm, Plane Reclaimers. I got in touch to ask if I could buy some 777 panels to wrap-around my sim set-up and block out those footballs.”

‘Captain’ McCombie poses for the camera; a multitude of controls includes radio, TCAS/transponder, evacuation, rudder trim and third CDU

The 1,100-mile quest

Plane Reclaimers went one better. “The guys invited me down to Wales and let me look around the retired cockpit,” says McCombie. “I was like a kid in a sweet shop. I thought to myself, I need it all,”

And with their help, that’s exactly what he got. He hired a van, drove the 1,100-mile round trip to collect his (rather heavy) bundle of aviation history – cockpit panels, ceilings and even the flight deck door. Back they went with him to a new home – no longer in his shed, but upgraded to the garage, where there was less risk of the rain getting in. Soon enough, the three TV screens were switched in for a wraparound 200° projector view, and the pilot’s seat was wired up to make it bump bump bump as the aircraft landed.

“When people ask me if I could fly a real plane, the answer is I’d never manage to land it, but I could certainly programme it”

So, what do people actually do in a flight simulator? Take a lap around their favourite city? For our wannabe pilot, half the thrill is in the set-up.

“It can be 30 minutes of programming before I’m even in the air: running checklists, preparing flight plans, weather considerations, making all manner of calculations,” explains McCombie. “When people ask me if I could fly a real plane, the answer is that I’d never manage to land it – but I could certainly programme it!”

The flight deck door seen from the inside and outside

Going the distance

As for his longest stint in the sim: “I’ve done a 14-hour flight in there,” he admits, “I mean, it is bonkers, but I like replicating flights I’ve done in real life. If I’ve just gone to Santiago, I’ll come home, get that scenery software and do it at home (with added loo and coffee breaks) – all the while watching the flight’s progress on my phone.”

So, what’s next for McCombie’s passion project? “It’ll always be a work in progress as new software develops,” he admits. “I’d like proper ATC in my headset, for instance, and I’ve got a telephone handset. I joke I’d love to be able to order a coffee from my wife – although I can only imagine the response I’d get!”

Speaking of his wife, does she approve? “Emma hates flying and doesn’t enjoy the sim at all. But she’s incredibly supportive of the hobby,” he says. When I ask McCombie if he’s donned a Captain’s hat yet, the reply comes back laughing: “I think that would be a step too far – even for me!”